Understanding the Formation of Bone Spurs in the Knee due to Advanced Osteoarthritis

Everything you need to know about the cause, symptoms and treatment options for bone spurs in the knee joint.

What is a bone spur?

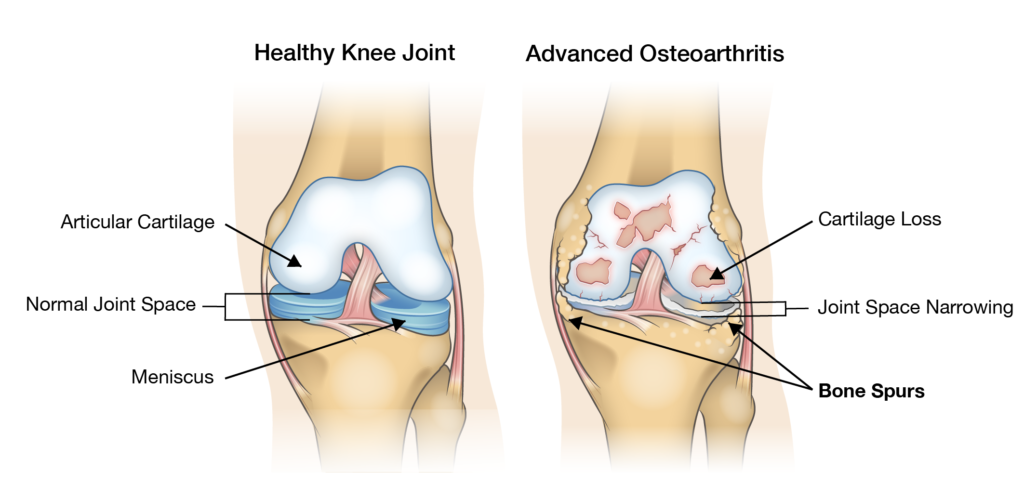

If you or someone you know has been diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis you’ve likely heard of osteophytes or as they are more commonly known, “bone spurs” and sometimes referred to as “spurring bone”. So, what is a bone spur? Bone spurs are abnormal bony lumps that appear on the surface of joints that have suffered some degree of cartilage loss. Through wear and tear, cartilage, the “cushioning” within the knee joint, slowly degrades resulting in the formation of bone spurs as your body adapts to maintain the stability of the knee joint.

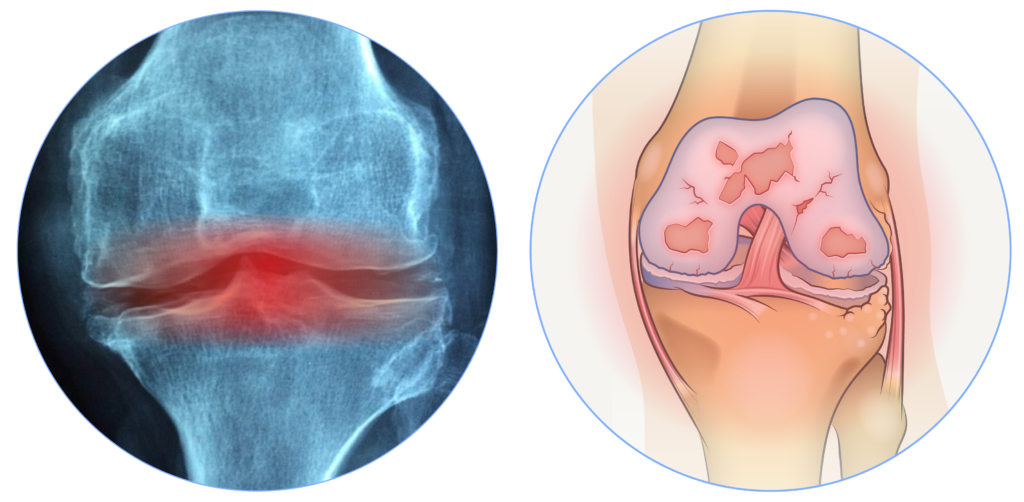

How are bone spurs diagnosed?

For those suffering from moderate to severe osteoarthritis, bone spurs can be a major contributor to pain and dysfunction. In these cases, diagnostic imaging is often used to examine the structure of the knee joint. Using X-ray imaging, physicians can assess the level of cartilage damage within the knee and identify the extent to which bone spurs have formed over the surface of the joint.

The ‘Kellgren and Lawrence Osteoarthritis Classification’ (KLOC)1 is commonly used by physicians to determine the severity of osteoarthritis. Information gathered from diagnostic imaging is examined using the KLOC criteria to provide a severity grade between 1-4. Those with ‘severe’ or ‘grade 4’ osteoarthritis will have multiple large bone spurs within the knee joint. Typically bone spur growth is observed around the joint line where cartilage has degenerated and has led to painful bone on bone friction.

How and why do bone spurs grow in the knee joint?

As cartilage degenerates, the bony surfaces of the knee cap (patella), the thigh bone (femur) and shin bone (tibia) begin to place direct pressure on each other. As bone on bone pressure occurs, a cascade of cellular reactions cause the formation of cells called “osteoblasts” which begin building new bone tissue in the areas where the bone has been damaged2. This is where osteoarthritis differs dramatically from another common arthritic condition called rheumatoid arthritis. Bone spurs do not occur in rheumatoid arthritis because the cellular processes involved are purely degenerative, causing virtually no bone growth at all4. Without the generation of new bone within the knee joint, it will erode and completely stop functioning4. You can think of spurring bone as a rough ‘patch job’ the body performs in response to joint damage and instability.

What are the risk factors for bone spur growth?

Bone Spurs in the knee form over long periods of time due to “wear and tear” on the knee joint. There are a variety of genetic and lifestyle factors that are known to contribute to their growth5. Due to the amount of time it takes bone spurs to form, age is a key consideration6. Almost everyone will have some sort of bone spur formation as they age.

Bodyweight and lifestyle factors may also increase the size and number of bone spurs on the knee. Elevated Body Mass Index 8 (BMI), heavy physical activity 9, and frequent kneeling and squatting 5 all contribute to excessive wear on the knee joint and bone spur formation. Preliminary evidence suggests that a variety of dietary deficiencies 9-10, low birthweight 12, and heritable genetic factors 13 may also contribute to the risk and progression of bone spur formation throughout the body.

How do bone spurs impact the function of the knee?

As the cartilage within the knee joint continues to wear away over time, the number and size of these bony protrusions increases in people with severe knee arthritis. While the growth of bone spurs may help maintain some structural stability around the knee joint, they usually cause a significant reduction in joint mobility and can be very painful. Unfortunately, this can negatively impact your ability to perform various recreational and daily-living activities. Movements that require significant amounts of knee joint mobility, like squatting, lunging and walking up and down stairs can become problematic. High impact activities such as running and jumping can aggravate the condition causing pain and speed up bone spur formation.

Those with bone spurs often avoid placing strain on the knee joint in an effort to reduce pain during high impact activities. As a result, sufferers of severe osteoarthritis usually lose strength in their thigh muscles (quadriceps and hamstrings). At this point, balance and stability during simple movements become impaired. Fortunately, there are a variety of options available to slow the progression of osteoarthritis, bone spur growth and their contribution to pain and dysfunction of the knee joint.

What are the treatment options for osteoarthritis and bone spurs?

When looking at treatment options it is important to consider the condition of the knee relative to current and future lifestyle demands. If pain and discomfort interfere with recreational activities, activities of daily living, mood and psychological health then an appointment with a physician to discuss treatment options is warranted. Since bone spurs and osteoarthritis progress over time prevention is also an important aspect to consider. Typically the earlier treatment is started the more successful it is in reducing pain and maintaining function.

Treatment can be divided into two categories: surgical and non-surgical. The former is usually reserved for patients with severe osteoarthritis where conservative treatment has failed to provide relief from symptoms. Surgical removal of osteophytes ranges from minimally invasive arthroscopic techniques to full knee replacements which can require up to 1 year of recovery time.

Arthroscopic Osteophyte Excision: This surgery involves a small incision in the knee joint where various medical tools are inserted to shave down bone spurs thought to be driving knee dysfunction. This surgery is recommended only in very specific scenarios and does not provide a long term solution. Also, there is a limited amount of research into its effectiveness14.

Partial or Total Knee Replacement: A surgery that involves completely replacing the weight-bearing surfaces of the knee joint. While very common, typically this is reserved for older patients with severe loss of quality of life and knee function. While it is effective in restoring function, the recovery time and rehabilitation can be both lengthy and costly.

Non-surgical treatment for spurring bone

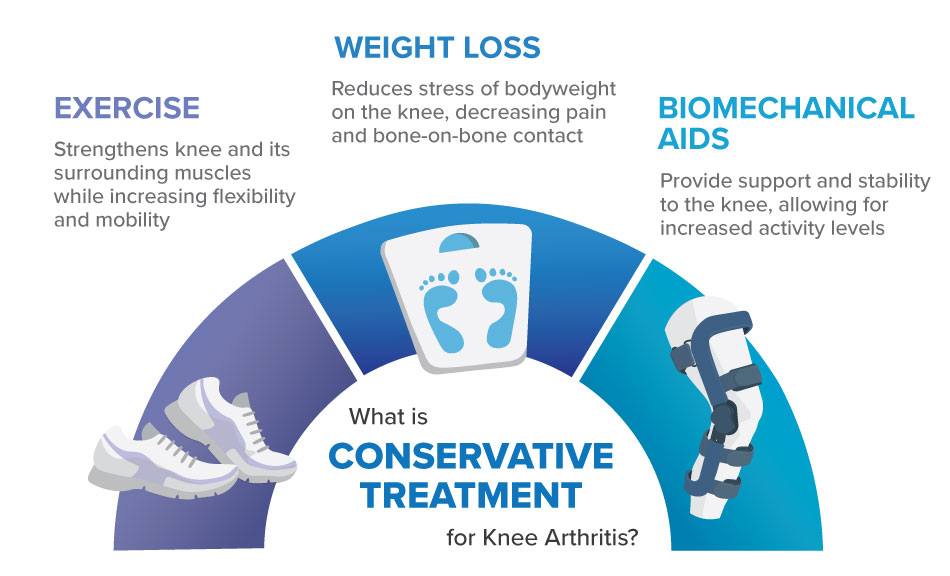

Conservative treatment is often successful and recommended before entertaining the idea of surgery. These strategies are typically categorized as pharmacological (using medication) and non-pharmacological (not using medication). While painkilling drugs can provide a great deal of relief, most experts agree that an accompanying management and prevention strategy is also desirable when treating osteoarthritis15-16.

Slowing the development and reducing the symptoms associated with bone spurs in the knee generally requires decreasing the physical demands on the knee joint itself. According to the International Osteoarthritis Research Society17 (see full OARSI recommendations here) weight loss can be one of the most effective and practical interventions especially if it is done early in life and sustained over time.

It has been established that both female18 and male19 athletes are at a higher risk for knee osteoarthritis and bone spur formation later in life. This may be particularly true for athletes participating in high impact sports that involve repetitive sprinting and jumping. For those interested in avoiding or delaying surgery so they can maintain a physically active lifestyle or occupation, a compelling case can be made for the use of a knee brace that helps reduce the load on the knee during repetitive or vigorous activity. If you were asking yourself “What is a bone spur and how does it impact my knee health?”, hopefully, this article has improved your understanding. To learn more about how your arthritis may develop and how you and your doctor could manage it read our comprehensive Guide to Severe Knee Arthritis.

DID YOU KNOW?

Tri-compartment Offloader Knee Braces can reduce joint contact forces in your knee by over 40%20. This dramatically reduces bone on bone pressure – the primary cause of painful bone spurs.

References

- Schiphof, D., Boers, M., & Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M. (2008). Differences in descriptions of Kellgren and Lawrence grades of knee osteoarthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 67(7), 1034-1036.

- Michael, J. W. P., Schlüter-Brust, K. U., & Eysel, P. (2010). The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Deutsches Arzteblatt International, 107(9), 152.

- Cicuttini FM, Baker J, Hart DJ, Spector TD. Association of pain with radiological changes in different compartments and views of the knee joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1996;4:143–7.

- Menkes, C. J., & Lane, N. E. (2004). Are osteophytes good or bad?. Osteoarthritis and cartilage, 12, 53-54.

- Wong, S. H. J., Chiu, K. Y., & Yan, C. H. (2016). Review Article: Osteophytes. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery, 24(3), 403–410. doi:10.1177/1602400327

- Snodgrass JJ. Sex differences and aging of the vertebral column. J Forensic Sci 2004;49:458–63.

- O’Neill TW, McCloskey EV, Kanis JA, Bhalla AK, Reeve J, Reid DM, et al. The distribution, determinants, and clinical correlates of vertebral osteophytosis: a population based survey. J Rheumatol 1999;26:842–8.

- Ozdemir F, Tukenmez O, Kokino S, Turan FN. How do marginal osteophytes, joint space narrowing and range of motion affect each other in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int 2006;26:516–22.

- Muraki S, Oka H, Akune T, En-yo Y, Yoshida M, Nakamura K, et al. Association of occupational activity with joint space narrowing and osteophytosis in the medial compartment of the knee: the ROAD study (OAC5914R2). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:840–6.

- Muraki S, Akune T, En-yo Y, Yoshida M, Tanaka S, Kawaguchi H, et al. Association of dietary intake with joint space narrowing and osteophytosis at the knee in Japanese men and women: the ROAD study. Mod Rheumatol 2014;24:236–42.

- Imagama S, Hasegawa Y, Seki T, Matsuyama Y, Sakai Y, Ito Z, et al. The effect of β-carotene on lumbar osteophyte formation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:2293–8.

- Clynes MA, Parsons C, Edwards MH, Jameson KA, Harvey NC, Sayer AA, et al. Further evidence of the developmental origins of osteoarthritis: results from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2014;5:453–8.

- Yamada Y, Okuizumi H, Miyauchi A, Takagi Y, Ikeda K, Harada A. Association of transforming growth factor beta1 genotype with spinal osteophytosis in Japanese women. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:452–60.

- Shin, C. S., & Lee, J. H. (2012). Arthroscopic treatment for osteoarthritic knee. Knee surgery & related research, 24(4), 187.

- Michael, J. W. P., Schlüter-Brust, K. U., & Eysel, P. (2010). The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Deutsches Arzteblatt International, 107(9), 152.

- Mohing W. Die Arthrosis deformans des Kniegelenkes. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1966.

- Zhang, W., Moskowitz, R. W., Nuki, G., Abramson, S., Altman, R. D., Arden, N., … & Dougados, M. (2007). OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis and cartilage, 15(9), 981-1000.

- Spector, T. D., Harris, P. A., Hart, D. J., Cicuttini, F. M., Nandra, D., Etherington, J., … & Doyle, D. V. (1996). Risk of osteoarthritis associated with long‐term weight‐bearing sports: a radiologic survey of the hips and knees in female ex‐athletes and population controls. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology, 39(6), 988-995.

- Kujala, U. M., Kaprio, J., & Sarno, S. (1994). Osteoarthritis of weight bearing joints of lower limbs in former elite male athletes. Bmj, 308(6923), 231-234.

- McGibbon, C. & Mohamed, A. Knee Load Reduction From an Energy Storing Mechanical Brace. Canadian Society for Biomechanics (2018).

Frequently Asked Questions

Bone spurs (osteophytes) in the knee are small bony outgrowths caused by excessive friction between the surfaces of the joint. This is most commonly caused by osteoarthritis which is characterized by a gradual loss in joint cartilage overtime.

Reducing your risk of degenerative joint disease (osteoarthritis) can be accomplished by regular light-moderate exercise, weight loss, and avoiding overly repetitive knee flexion movements (squatting, lunging).

It is possible to remove bone spurs from the knee joint, however, in cases where there many bone spurs spread across the joint surface most surgeons prefer to perform knee replacement surgery During this procedure, the internal bony surfaces of the knee joint are shaved down to accommodate the installation of a metal prothesis.